Image taken from : eltiempo.com

This workshop leader and human rights defender has not been heard from since November 1992. Story.

On Wednesday, November 4, 1992, the workshop leader and human rights defender Gustavo Salgado Ramirez accompanied his daughter, Juana Ibanaxca Salgado, to the school route in Bogota. It was a new routine, adopted for security reasons, because months before, Juana, then 15 years old, was the one who answered the phone and received the threat: either Gustavo stopped his work or they would kill him.

Taking the bus to school was no longer an option. “He tried to insure me and not him,” Juana recounts about the last day she saw her father, whom she remembers with sweetness and with whom she had a very close, attached relationship.

“I was lucky to have him very close in my upbringing. I have a tender memory of him, he was always very close to the world of art and sports. He was waiting for me training boxing while I was in the gymnastics line,” Juana adds.

Among her memories are trips to the National Park in Bogota to see theater, something that awakened her sensitivity in the arts, her personality, and her discipline. Historian, dancer and activist, Juana Salgado is part of an artistic collective called ‘La Otra Danza’ from which she has explored the terrible silent struggle of impunity against oblivion, in favor of memory.

Gustavo Salgado Ramirez worked for the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, or Limpal, and ‘Terre de Hommes’, human rights organizations that conducted training workshops for vulnerable youth. That November 4, 1992, he left his home around 8 a.m. from north to south. His wife, Patricia Jimenez, gets off at 72nd to classes at the Pedagogical University and they say goodbye. He told her that he was going to the office and from there to some workshops, but he never arrived.

“He disappeared between 72nd and 53rd because the office was on 53rd and Caracas. The last person who sees Gustavo is his wife, they say goodbye on the bus, and from then on nothing is known”, says lawyer Yessika Hoyos of the Lawyers’ Collective ‘José Alvear Restrepo’, who is handling the case.

In addition to the threatening call, family and friends know that just two days before, two investigators from the now extinct Administrative Department of Security (DAS) had gone to Limpal’s offices and had been asking for Gustavo, but also for Gabriel Angel Betancur, and Teresa Quiñones, who were partners and worked with him. And Ute Sodeman, a German citizen who was the president of Limpal and representative of ‘Terre de Hommes’.

It is very difficult when you find institutions that don’t really care about the disappeared. You can’t disappear a person who was previously followed and no one knows what happened. They, “had already denounced surveillance and were the ones who reported Salgado’s disappearance to the justice system” says lawyer Hoyos.

Betancur Alliegro, a peasant leader, and Quiñones Castañeda, a Fine Arts graduate, who gave their statements at the time, were forcibly disappeared in 1998. And Sodeman left the country in fear and anxiety.

In November, the case completed 29 years of impunity and oblivion. In the judicial files, there is an intelligence report from units of the National Army in which the names of Betancur and Quiñones appear and another one in which Gustavo and Limpal appear in relation to surveillance.

The hypothesis before the justice system for the family is only one, that it was a “joint operation of the Army with the DAS”, sponsored under the logic of the ‘internal enemy’, but nothing of substance has happened.

In 2013 there was a change of prosecutor and some evidence was ordered that attracted attention, such as, for example, that some records were asked to Medicina Legal of some missing persons, whose initial response was that a body had arrived under the name of Gustavo Salgado and then, the entity assured that it was a mistake, that the victim was identified as another person.

“We go to Medicina Legal to ask why they believe that a body with that name enters. An official who does not even corroborate with whom she answered the past (to the Prosecutor’s Office), says no, that there was a mistake. That there was a comparison of that body and it was discarded”, explains the lawyer.

Today, the case is in the Human Rights Unit of the Attorney General’s Office. “It is very difficult when you find institutions that do not really care about the disappeared in Colombia. The current prosecutor Francisco Barbosa is not interested in the disappeared, it is necessary to investigate in context. You can’t disappear a person who was previously followed and nobody knows what happened. The disappeared are missing for all of us,” says Hoyos.

Image:

Private archive

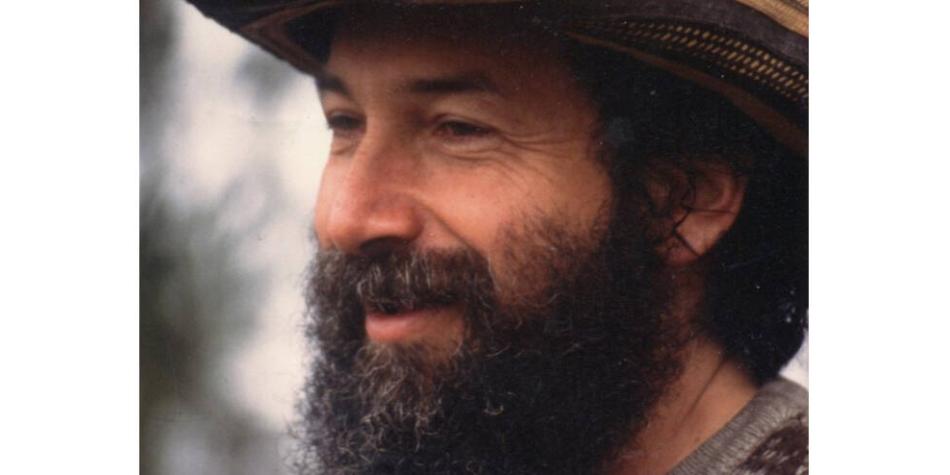

Gustavo Salgado, forcibly disappeared, and his daughter Juana Salgado

The wound

“It’s like walking around with an open wound. I have always felt this way, incomplete, not knowing what happened to him, being separated from my family. My mother and my (two) sisters had to leave and I was left alone here, practically separated from them for many years for security, for life security because there was no psychological security,” adds Juana, who emphasizes that it took her years to be able to talk about this painful situation with the firmness with which she does it now.

She grew up with a lot of anger, she remembers, and had to face the indolence of society at the age of 15. For example, when her father’s disappearance was in the news and her mother tried to get the school to give her a scholarship for grades 10 and 11, the school where she had studied ‘all her life’ kicked her out.

“That hurts a lot. It hurts the way of seeing a human rights defender in the 1990s and the way we were mistreated: colleagues who stop talking to you, the same family and the very polarized readings of people, although now human rights defenders are valued a little more,” she says.

“I had to go through many processes to understand, but I will never stop claiming all the injustice, impunity and invisibility. And not only from the State, but also from a citizenry that has never been aware of the number of disappeared people in this country”, says Juana, who has among her memories her father in the march, interested in science and technology, in communications.

“He was a guy who was very forward-thinking about politics but also about the relationship between politics and nature,” he adds. An extroverted character, striking with the way he dressed, who did not always match what he wore. “I enjoyed my dad a lot, my sisters were little girls. I have a very strong imprint of him in my wound,” Juana says.

Gustavo Salgado’s family found in the arts a way to exorcise that open wound. “The oldest hours” (Las horas más antiguas), an audiovisual production, pays a solemn tribute to the father, the husband, the grandfather, using, among others, a text by Gustavo, who will be 76 on June 3, 2022.

Las horas más antiguas from Desaparicionforzada.com on Vimeo.

The work ‘Camino a Casa‘ by the collective La Otra Danza presents its protagonist, Aimara, as she brings her missing father to tour the city transformed into a giant lion.

Juana, who has participated in seminars on forced disappearance, not only calls for justice but also for a social awakening regarding the transition process the country is going through. For example, she draws attention to the process of memory that Argentina went through after the last military dictatorship (1976-1983).

“The disappeared are on the walls, there are museums, there is a citizenry that is ashamed of what happened and here we are in a process that is too slow. So far I feel that citizens are realizing that we are stepping on dead people all the time and that the forced disappearance happened in the eyes of all of us and that the State is absolutely vulgar, cynical and shameless because it has used the disappearance as a way to silence other voices that are divergent from those of the State”, he specifies.

Salgado, along with other collectives that fight for the memory of the victims of forced disappearance, were responsible for a mural that was made on Carrera Séptima, on the road, as part of the national strike of 2021, in front of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace in May 2021.

The large-scale mural, clearly visible from above, read “Desaparecidxs, ¿Dónde están?”, and on one side it had the number of people who had disappeared at the time of the birth and, on the other, the estimated global universe of victims of the scourge: 82,472. In the process, says Juana Salgado, people approached her to ask what a disappeared person was and days later it was erased.

“There are many challenges at a symbolic level, but that implies resources and political will, generally it is the lawyers and family pulling the cases. I think we have to strengthen pedagogy,” Juana concludes, convinced that her father’s case, like those of others who disappeared at the same time, in which the alleged perpetrators are state agents, also involved “taking away beautiful generations who wanted to change this country, even those who are passing away now. Any person can be the object of disappearance in this country”.

The call for justice

Lawyer Yessika Hoyos made a strong appeal to the Attorney General’s Office for this case, as well as those of Gabriel Betancur and Teresa Quiñones. As she told EL TIEMPO, in her opinion, the current head of the entity, Francisco Barbosa, “is not interested in the disappeared”.

“If prosecutor Barbosa had a policy to search for the disappeared he would strengthen the team, he would not be, on the contrary, ending the Human Rights Unit. I want to call on him to strengthen the unit because they are filing the investigations of forced disappearance and forced displacement,” he said.

He also explained that it was found that the Quiñones case was archived and only when they went to a tutela, the Prosecutor’s Office explained that the file did not appear either. “Then it says that they found something and they send 50 pages, that is not the investigation because that is where another Army intelligence report was found, where a list appeared with other human rights defenders such as Alirio Uribe.”

Hoyos recalled that the duty to investigate lies with the State and not with the relatives or their representatives. “It is a totally indolent attitude, of not caring about the disappeared,” he added.

The jurist pointed out that, despite denials, State crimes do exist in Colombia and “this construction of the internal enemy has facilitated the declaration of military objectives. We need to know the truth so that we know as a society what happened and what we cannot allow to happen again”.

JUSTICE

Image from eltiempo.com